EUCHARIST AND ECOLOGY

(Denis Edwards)

How do ecological issues, such as global climate change, impact on our celebrations of the Eucharist? How is eucharistic worship related to ecological action and life-styles? What is it to live an ecological vocation before the God of Jesus Christ? What is the relationship between ecological practice and Christian spirituality? In this last chapter I will attempt a response to these questions, taking up, first, some suggestions for an ecological theology of the Eucharist, and then some reflections on spirituality and praxis. How do ecological issues, such as global climate change, impact on our celebrations of the Eucharist? How is eucharistic worship related to ecological action and life-styles? What is it to live an ecological vocation before the God of Jesus Christ? What is the relationship between ecological practice and Christian spirituality? In this last chapter I will attempt a response to these questions, taking up, first, some suggestions for an ecological theology of the Eucharist, and then some reflections on spirituality and praxis.

Towards an Ecological Theology of the Eucharist.

The proposal advanced in this section is that, when Christians gather for Eucharist, they bring the Earth and all its creatures, and in some way the whole universe, to the table. I will explore this proposal by working though fives steps: Eucharist as the lifting up of all creation, as the living memory of both creation and redemption, as sacrament of the cosmic Christ, as participation with all God’s creatures in the Communion of the Trinity, as anticipation of the participation of all God’s creatures in the life of the Trinity and as solidarity with the victims of climate change and other ecological crises.

The Lifting Up of All Creation

Like many Othodox theologians, he sees human beings as called by God to be “priests of creation.” He distinguishes this priestly task from notions of sacrificial priesthood that he associates with medieval and Roman Catholic theology. He sees each baptised person as called to be, like Christ, a fully personal being. This involves being relational rather than self-enclosed, being able to go out of self to the other, in what he calls ek-stasis. Persons are always ecstatic, in the sense that they achieve personhood only in communion with others. Humans are relational beings. Their vocation is to relate in a fully personal way to God, to other humans and to other creatures of God. According to Zizioulas, humanity and the rest of creation comes to their completion in the life of God through each other.

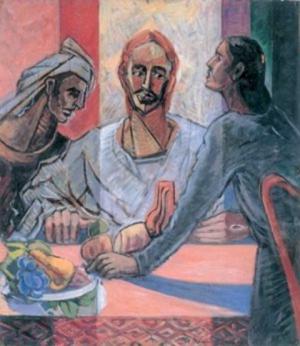

When humans come to the Eucharist, they bring the fruits of creation, and in some way the whole creation, to the eucharistic table. In the Eucharist, creation is lifted up to God in offering and thanksgiving. The gifts of creation are lifted up to God and the Spirit is invoked to transform the gifts of creation, and the assembled community, into the Body of Christ. The exercise of this priesthood is not confined to the ordained but is the God-given role of all the faithful. It is not restricted to liturgical celebrations but is meant to happen in the whole of life. It is meant to involve all human interactions with the rest of creation. When humans come to the Eucharist, they bring the fruits of creation, and in some way the whole creation, to the eucharistic table. In the Eucharist, creation is lifted up to God in offering and thanksgiving. The gifts of creation are lifted up to God and the Spirit is invoked to transform the gifts of creation, and the assembled community, into the Body of Christ. The exercise of this priesthood is not confined to the ordained but is the God-given role of all the faithful. It is not restricted to liturgical celebrations but is meant to happen in the whole of life. It is meant to involve all human interactions with the rest of creation.

Long ago Louis Bouyer pointed out that the early Christian eucharistic prayers had their origins and models in Jewish prayer forms used in synagogues and especially in homes, above all in the Passover meal. These prayers begin with a blessing of the gifts of creation. They are based on the memory of and thanksgiving for God’s work that involves both creation and salvation. Zizioulas makes the same point, insisting that all the ancient eucharistic liturgies began with thanksgiving for creation and then continued with thanksgiving for redemption in Christ, and all of them were centred on the lifting up the gifts of creation to the Creator.

When we come to the Eucharist we bring the creatures of Earth with us. We remember the God who loves each one of them. We grieve for the damage done to them. We feel with them. We can begin to learn the kind of ethos that Zizioulas speaks of, an ethos that leads to a different way of acting.

We remember the vulnerable state of the community of life on Earth today and bring this to God. All of this is caught up in the mystery of Christ celebrated in each of our Eucharists In the great doxology at the end of the eucharistic prayer, we lift up the whole creation through, with and in Christ, “in the unity of the Holy Spirit” to the eternal praise and glory of God.

Sacrament of the Cosmic Christ

The Christ we encounter in the Eucharist is the risen one, the one in whom all things were created and in whom all are reconciled (

Col 1:15-20). God’s eternal wisdom and plan for the fullness of time is “to gather up all things in him, things in heaven and things on earth” (Eph 1:10). Even when, in the Eucharist, the focus of the memorial is on Christ’s death and resurrection, this is not a memory that takes us away from creation. On the contrary, it involves us directly with creation. It connects us to Earth and all its creatures.

When we remember Christ’s death, we remember a creature of our universe, part of the interconnected evolutionary history of our planet, freely handing his whole bodily and personal existence into the mystery of a loving God. When we remember the resurrection, we remember part of our universe and part of our evolutionary history being taken up in the Spirit into God. This is the beginning of the transformation of the whole creation in Christ. The Eucharist is the symbol and the sacrament of the risen Christ who is the beginning of the transfiguration of all creatures in God. In eating and drinking at this table we participate in the risen Christ (1 Cor 10:16-17). When we remember Christ’s death, we remember a creature of our universe, part of the interconnected evolutionary history of our planet, freely handing his whole bodily and personal existence into the mystery of a loving God. When we remember the resurrection, we remember part of our universe and part of our evolutionary history being taken up in the Spirit into God. This is the beginning of the transformation of the whole creation in Christ. The Eucharist is the symbol and the sacrament of the risen Christ who is the beginning of the transfiguration of all creatures in God. In eating and drinking at this table we participate in the risen Christ (1 Cor 10:16-17).

All matter is the place of God. All is being divinized. All is being transformed in Christ: “Through your own incarnation, my God, all matter is henceforth incarnate.” Because of this, Earth, the solar system and the whole universe become the place for encounter with the risen Christ: “Now, Lord, through the consecration of the world, the luminosity and fragrance which suffuse the universe take on for me the lineaments of a body and a face—in you.”

Participating with All God’s Creatures in the Communion of the Trinity.

Every Eucharist is an eschatological event, meaning that it is an event of the Spirit that anticipates the future when all will things will be taken up into divine Communion. The Eucharist is profoundly trinitarian. Our eucharistic communion, our communion with each other in Christ, is always a sharing in and a tasting of the divine Communion of the Trinity, in which all things will be transfigured and find their eternal meaning and their true home. This trinitarian Communion which we share is the source of all life on Earth; it is what enables a community of life to emerge and evolve; and, in ways that are beyond our imagination and comprehension, it is what will be the fulfillment of all the creatures of our planet, and all the wonders of our universe. As we participate in the Eucharist, we taste in anticipation the fulfillment of all things taken up into the divine life of the Trinity.

This means, as Tony Kelly has said, that the “most intense moment of our communion with God is at the same time an intense moment of our communion with the earth.” By being taken up into God, we are caught up into God’s love for the creatures of our planetary community. This begins to shape our ecological imagination: “The Eucharist educates the imagination, the mind, and the heart to apprehend the universe as one of communion and connectedness in Christ.” In this eucharistic imagination, a distinctive ecological vision and commitment can take shape. With this kind of imagination at work in us, we can see the other creatures of Earth as our kin, as radically interconnected with us in one Earth community of life before God. We can begin to see critically – to see more clearly what is happening to the Earth. We are led to participate in God’s feeling for the life-forms of our planet. An authentic eucharistic imagination leads to an ecological ethos, culture and praxis.

Solidarity with Victims

The Eucharist always involves the memory of the cross. The theologian Johannes Metz speaks of this as a “dangerous” memory. The cross of Jesus is an abiding challenge to all complacency before the suffering of others. It brings those who suffer to the very centre of Christian faith. It challenges self-serving and ideological justifications of the misery of the poor and the victims of war, oppression and natural disasters. The resurrection offers a dynamic vision of hope for the suffering of the world, but it does not dull the memory of the suffering ones. They are always present, forever imaged in the wounds of the risen Christ.

The Eucharist, as a living memory of all those who suffer, calls the Christian community to a new solidarity that involves all the human victims as well as the animals and plants that are destroyed or threatened. Solidarity involves personal and political commitment to both of the two strategies that have been identified as responses to climate change, those of mitigation and adaptation. Adaptation will mean re-ordering society, budgeting in readiness for ecological disasters, training personnel and allocating resources. In a particular way it will involve, as a matter of justice, hospitality to environmental refugees.

When we Australian Christians gather for eucharistic celebrations, we gather in solidarity with Christians who assemble for Eucharist in Kiribas, in Tuvalu, and in

Bangladesh. We gather in solidarity with those who share other forms of religious faith in the Pacific, in South-East Asia, in

Africa, and in all parts of our global community.

We pray in solidarity with the global community, that the Eucharist that brings us into peace and communion with God, may “advance the peace and salvation of all the world” (Third Eucharistic Prayer). We commit ourselves again to discipleship, to an ecological ethos, lifestyle, politics and praxis, as people of Easter hope.

We encounter Jesus, in all the healing, liberating love poured out in his life and death and know again his presence as the risen one transforming all things from within. In the power of the Spirit, we participate in and taste the eschatological Communion of the Trinity. In the Spirit, the assembly is made one in Christ, in a communion in God that has no borders, but reaches out to embrace all of God’s creatures. Every Eucharist calls us to ecological conversion and action.

|